TIPA: 'Plastic' film you can compost

By Ruth Schuster

Haaretz, Israel

Many wonderful things, from chocolate to cars, may fleetingly boost our well-being but ultimately bear a heavy price, whether to our thighs or to the planet. One of the most irreconcilable is plastic.

It's a bitter irony that plastic lives up to its hype: it really does isolate your sandwich from the environment, and it lasts forever. Moreover, recycling isn't going to save the whales. We may religiously discard bottles in recycling bins, but the fact is that most plastic is not even recyclable.

Among the worst offenders we barely notice is the plastic film that wraps everything from organic granola to socks.

No practical technology exists to recycle plastic film. If we toss it out with bottles, the recycling plants shrug, weed out the bottles by machine and throw the rest into landfills, explains Merav Koren. She is marketing director for TIPA, an Israel-based company that aims to change all this by making 100 percent compostable packaging film.

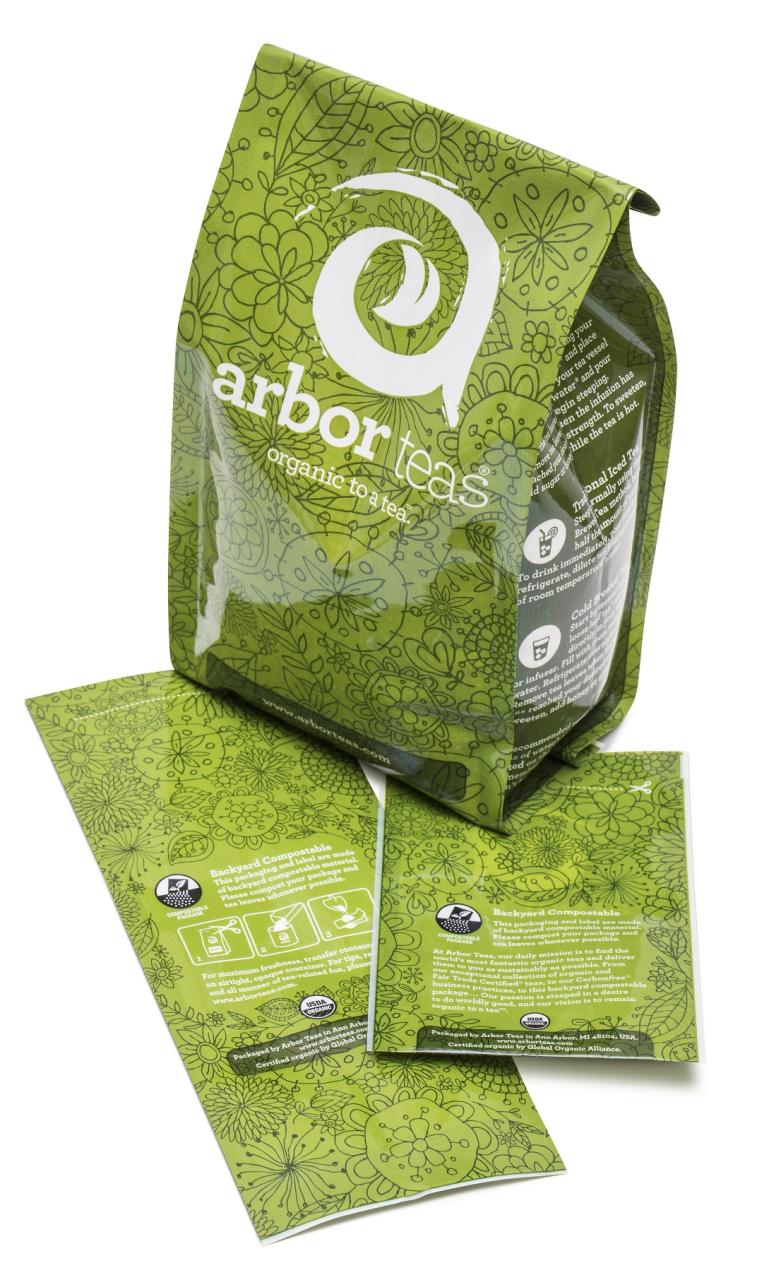

"TIPA films look like plastic and behave like plastic but end life like an orange peel," says Koren. Every aspect of it, from the packaging's film to its adhesive, is 100 percent compostable. Not a molecule will be added to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch located between Hawaii and California.

Part of aspiring to save the planet means manufacturing locally. TIPA film is deliberately made using the same machinery used to manufacture conventional plastic, and also using fossil fuels as a source - as well as plant materials, says founder and CEO Daphna Nissenbaum. The crux is that mass-manufacturing machines can be tweaked quickly to make TIPA films. "This model enables us to manufacture where target markets grow, for instance Germany and Italy," Nissenbaum, 51, explains. As its technology catches on and grows more affordable, the company can ramp up quickly to global levels.

But unlike conventional plastic, this wrapping will not stay with us and our children's children forever more. Under the right conditions for composting, TIPA packaging disintegrates into water, carbon dioxide and organic matter that bacteria then degrade, leaving nothing behind.

How would consumers know to throw the films out with organic leavings? The packaging bears a stamp saying so.

Compost is made by sticking organic waste into a bin or a hole in the ground. Leave it there, occasionally moistening and turning it over with something like a pitchfork. Under optimal conditions, in about 180 days, you have compost, which then serves as soil nutrient.

That said, modern urban households have many modern conveniences, such as running water, but let's face it, most lack gardens, let alone composters. Very few homemakers separate organic waste.

To this, Nissenbaum points out that one does not build a company for today's problems and environment but tomorrow's, and the world has realized that waste handling has to change because we're destroying the planet. Regulation, notably in Europe and China, is advancing towards requiring separation of all organic waste.

No need to worry – if TIPA film is tossed out with the regular trash, it will still degrade in the city dump. Like orange peel, unless you decide to mummify and frame it, it will ultimately disappear from your life.

TIPA began developing the compostable film in 2012, achieved certification, as all packaging for food requires, and in 2016 began selling to manufacturers and converters (which package products for manufacturers), chiefly in Europe. Sales grew fourfold in 2017 compared to the prior year, Koren says. The company now has 30 employees.

Price depends on the type of film ordered (the thinner, the cheaper) and other parameters, but may range from a bit more than conventional plastic to a lot more, mainly because the precursor polymers are still relatively expensive. However, the more the technology gains traction, the more affordable it should become, Koren predicts.

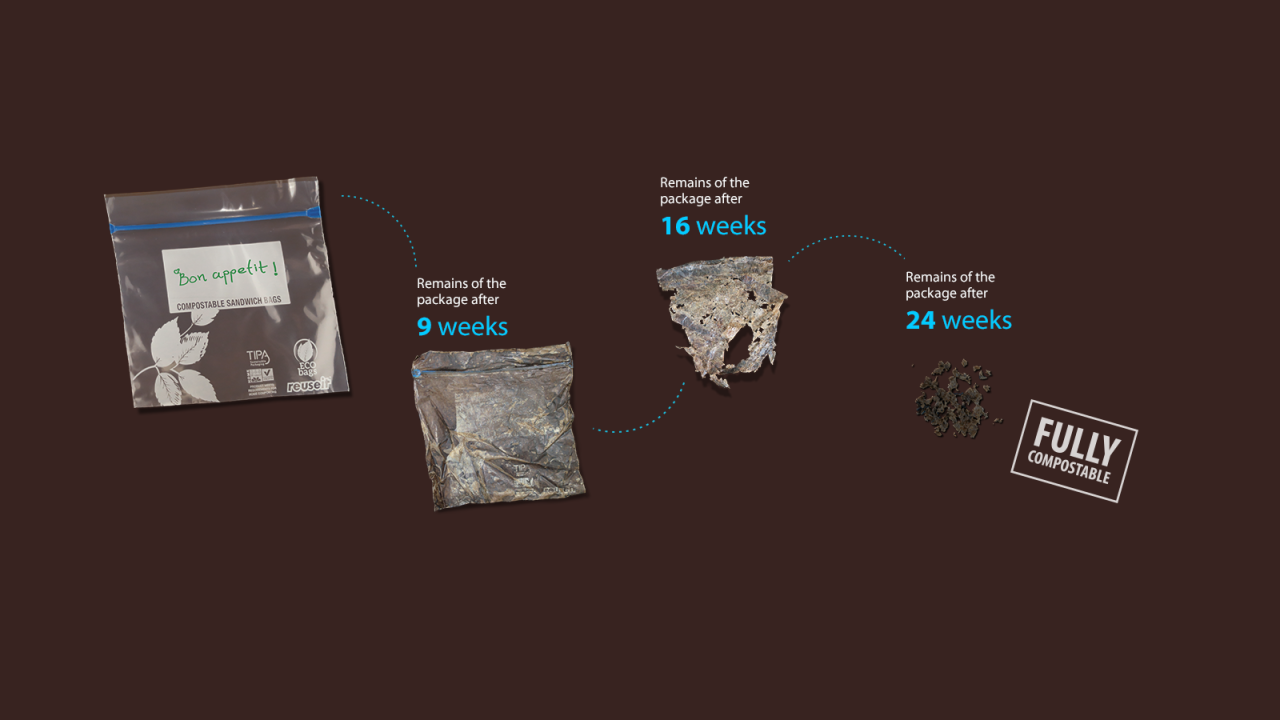

Make no mistake; in a compost heap or the trash, TIPA films take their sweet time to fall apart. That is precisely the necessary compromise between the requirements of the manufacturer – that its product remain protected (or bundled) until bought and used – and the requirements of the planet, that the wrapping not emulate diamonds and be forever.

Under appropriate conditions, TIPA films take up to six months to turn into compost, Koren says. Under sub-ideal conditions, which are all other circumstances, the key word is "eventually." But that means years rather than millennia, unlike conventional plastic.

If left sitting on a shelf, the TIPA wrapping starts to degrade only after about a year. That's more than enough for most foodstuffs (and doesn’t really matter for socks, especially if nobody is wearing them). It starts to look a little like a piece of paper left outside, cracking and browning around the edges. Gradually the whole thing falls apart. Crucially, at no point in this degradation process do the TIPA films produce microbeads, which notoriously get into every nook and cranny of the Earth, even the deepest oceans. As they degrade, TIPA films aren't gorgeous, but then they are gone as a packaging for all time.

Here we are to serve you with news right now. It does not cost much, but worth your attention.

Choose to support open, independent, quality journalism and subscribe on a monthly basis.

By subscribing to our online newspaper, you can have full digital access to all news, analysis, and much more.

You can also follow AzerNEWS on Twitter @AzerNewsAz or Facebook @AzerNewsNewspaper

Thank you!